Real and complex numbers in space

This is not a math tutorial. See Why am I writing about math?

Real numbers () are numbers that exist on the number line.

Understanding dimensions #

The physical world has three dimensions.

A sheet of graph paper (ignoring its thickness) is conceptually a two dimensional object.

A number line is a 1 dimensional object.

To describe a point on the number line only requires a single coordinate.

To describe a point on a Cartesian plane requires two coordinates.

To describe a point in space requires three coordinates.

The dimensionality of an object could be considered as the degrees of freedom that the object has.

Complex numbers are two dimensional #

Complex numbers (numbers in the form ) can be represented a points on the complex plane. The complex plane maps to a 2D Cartesian plane. The horizontal x-axis represents the real part of a complex number. The vertical y-axis represents the imaginary part of the complex number.

See notes / Introduction to imaginary numbers

Visualizing complex numbers #

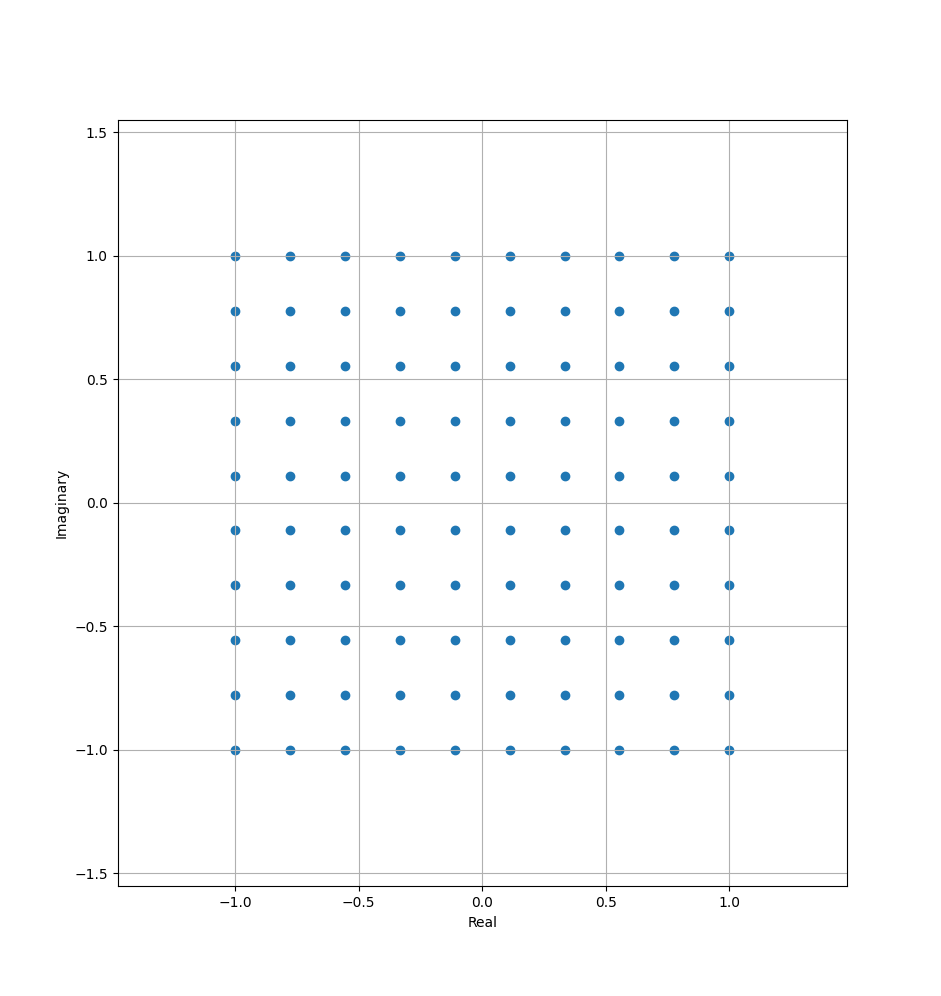

The following code creates a 10x10 grid of complex numbers, with the real plane in the range

(-1, 1) and the real part of the complex plane also in the range (-1, 1):

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

xmin = -1.0

xmax = 1.0

ymin = -1.0

ymax = 1.0

width = 10

height = 10

x = np.linspace(xmin, xmax, width)

y = np.linspace(ymin, ymax, height)

X, Y = np.meshgrid(x, y)

Z = X + 1j * Y

# Scatter plot the points on the complex plane

plt.scatter(Z.real, Z.imag)

plt.xlabel("Real")

plt.ylabel("Imaginary")

plt.axis("equal")

plt.grid(True)

plt.show()

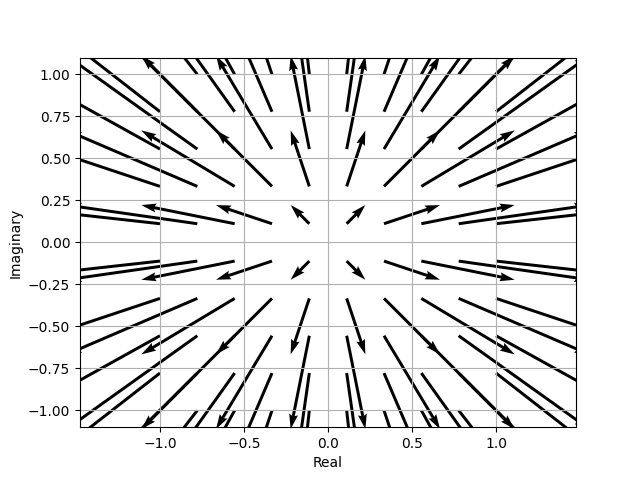

Complex numbers can be visualized as vectors.

# A quiver plot is a 2D graph that displays a field of vectors as arrows.

# quiver([X, Y], U, V, [C], /, **kwargs)

# X, Y define the arrow locations, U, V define the arrow directions.

# The `angles` arg sets the direction of the arrows; "xy": arrows point from (x, y) to

# (x+u, y+v)

plt.quiver(

Z.real, # arrow X coordinate start

Z.imag, # arrow Y coordinage start; the r part of the imaginary number

Z.real, # point arrows in the direction of the complex number

Z.imag, # point arrows in the direction of the complex number

angles="xy",

scale_units="xy",

scale=1,

)

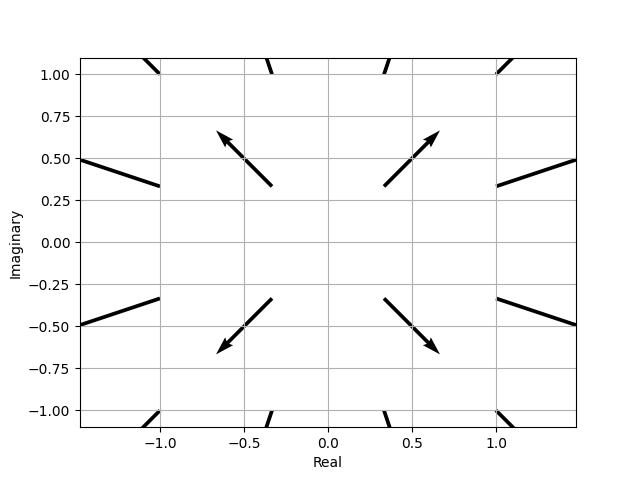

Here’s a scaled down version of the complex numbers that are being used in these examples. It’s a 4x4 grid instead of a 10x10 grid:

[[-1. -1.j -0.33333333-1.j 0.33333333-1.j 1. -1.j ]

[-1. -0.33333333j -0.33333333-0.33333333j 0.33333333-0.33333333j 1. -0.33333333j]

[-1. +0.33333333j -0.33333333+0.33333333j 0.33333333+0.33333333j 1. +0.33333333j]

[-1. +1.j -0.33333333+1.j 0.33333333+1.j 1. +1.j ]]

Calculating the angle for a complex number (also called the argument or phase) #

Starting from a complex number in the rectangular form: -0.33333333-1.j

Identify the components:

- real part:

-0.33333333 - imaginary part:

-1.0

The number is a + bi = -0.33333333-1j

Visualize (imagine for now) the number on the complex plane:

x = -0.33333333, y = -1.0. The number is in the third quadrant, both x and y are negative.

Calculate the angle of the point:

The simple approach with Python is theta = np.arctan2(y, x), or theta = np.angle(-0.33333333-1j)

In [10]: np.angle(-0.33333333-1j) # np.float64(-1.8925468781915389)

Out[10]: np.arctan2(-1, 0.33333333) # np.float64(-1.8925468781915389)

Note that np.angle returns the angle of a complex number in radians, np.arctan2 returns the

angle of (opposite, adjacent), (x, y), (real, imag).