Literary Machines (book)

- Website: http://www.thetednelson.com/literarymachines.php .

- Internet archive: https://archive.org/details/literarymachines00nels (a PDF of the book can be downloaded from the internet archive.)

- Project Xanadu website: https://www.xanadu.net/

Related to:

- notes / Transclusion — rendering multiple HTML fragments in a document

- notes / Literary Machines (chapter two)

As I’ve been reading the Literary Machines, what Ted Nelson is saying is jiving with me more and more. What follows is a lot of quotes with little commentary. There are more quotes than is probably allowable in terms of “fair use.” In my defence, the purpose of the quotes is to use them in my own little hyperlink experiment. Also, I’m typing the quotes out by hand from the version of the book that’s on the Internet Archive. Also, no one reads my blog. The book seems to be out of print. I see a few listings for it on AbeBooks (although that won’t get money to the author): https://www.abebooks.com/9780893470555/Literary-Machines-Theodor-Holm-Nelson-0893470554/plp .

Literary Machines: hypermedia at large (chapter 0) #

“…by ‘hypertext’ I mean non sequential writing—text that branches and allows choices to the reader, best read at an interactive screen.”1

“As popularly conceived, this is a series of text chunks connected by links which offer the reader different pathways.”2

“I will not argue with this definition here, but I hope it will become clear throughout the book how much more I think hypertext can be.”3

Most general writing #

“Hypertext can include sequential text, and is thus the most general form of writing. Unrestricted by sequence in hypertext we may create new forms of writing which better reflect the structure of what we are writing about; and readers, choosing a pathway, may follow their interests or current line of thought in a way heretofore considered impossible.”4

Computer text systems are in a calamitous state. (in 1987!) The world of paper is at least unified and compatible.5

Computer text (from different sources/applications) is not unified and compatible.

“I propose a third approach: to unify and organize in the right way, so as to clarify and simplify our computer and working lives, and indeed to bring literature, science, art and civilization to new heights of understanding, through hypertext.”6

“As the most general form of writing, hypertext will not be ‘another type’ of obscure structure, but a framework of reunification.”7

Project Xanadu #

Project Xanadu: the plan was (is?) to develop a hypertext system to support all the features of “these other systems” (referring to the disorganized state of computer text systems).

The project began in the fall of 1960. A prototype was put online in January 1987.

They hoped (hope?) to offer three versions:

- a single-user version

- a network server for offices

- a public access system “to be franchised like hamburger stands”8

Technical details (1987) #

The back-end program runs on a Sun Workstation under Unix. It’s written in C and compiles to about 137k of 68000 native code on Sun (not including buffer space). They recommend 1 MB of buffer space.

Front-end programs should include their protocol manager, a module which handles sending and receiving in the FEBE™ Front End-Back End protocol. It compiles to about 30K.

Why it’s taken so long to develop #

“The reason it has taken so long is that all of its ultimate features are a part of the design. Others begin by designing systems to do less, and then add features; we have designed this as a unified structure to handle it all. This takes much longer but leads to clean design.”9

The design problem is interesting to me, as I’m interested in the ideas but also want to get something done. What I’m considering is only somewhat related to project Xanadu though. Almost 40 years later (January 2026) I see real downsides to large scale unified systems. What interests me is the general idea of hypertext, the idea of allowing readers to create contexts through connecting text in one of a large number of possible sequences.

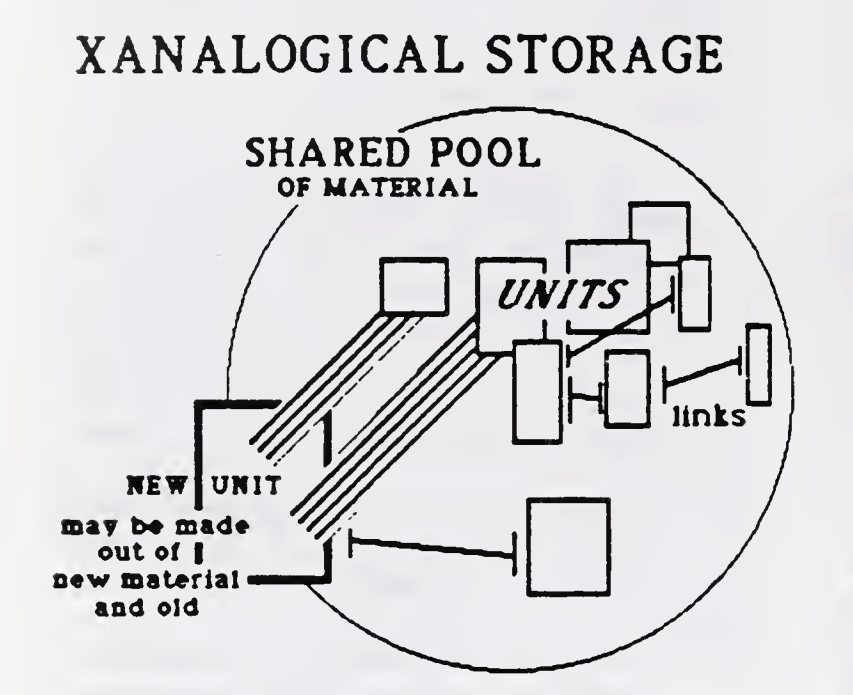

The structure: xanalogical storage #

“The Xanadu system is a unique form of storage for text and other computer data. The system is based upon one pool of storage, which can be shared and simultaneously organized in many different ways.”10

“This makes it possible to make new things out of old, sharing material between units.”11 (Emphasis is in the original, but it’s also what I’m interested in.)

Let’s see if my goals align with the author’s:12

-

all materials are in a shared pool of units, but every element has a unit in which it originated;

-

new units can be build from material in previous units, in addition to new material;

-

there can be arbitrary links between arbitrary sections of units.

“We call this ‘xanalogical storage’ (not a trademark).”13

Aside: my proposed structure #

-

all materials are in a shared pool of units, but every element has a unit in which it originated (a markdown file on my computer is built into a single HTML file and is chunked into HTML fragments, based on the markdown/HTML heading structure. Relative links in the fragment are absolutized to make the fragments independent of the original document.)

-

new units can be build from material in previous units, in addition to new material. Tentatively, new units can be built by selecting sections from the original HTML files, or by selection fragments returned from semantic search. The “new units” can be downloaded as markdown files. Once downloaded to a local computer, the computer’s owner can do anything they wish with the documents, including adding new material to them and uploading the revised documents to their own server/website.

-

there can be arbitrary links between arbitrary sections of units. This needs some thought. In contrast to my statement that “relative links in the fragments are absolutized,” to allow new documents to function independently of the original website, local links within the new document should be relative. Links to anything outside the new document should be absolute.

The three basic relationships of xanalogical storage #

The basic relationships:14

-

origin: the parts where elements begin

-

commonality: the sharing of elements between units

-

links: which mark, annotate and connect portions of units

The aspiration of project Xanadu #

“The Xanadu system, designed to address many forms of text structure, has grown into a design for the universal storage of all interactive media, and, indeed, all data; and for a growing network of storage stations which can, in principle, safely preserve much of the human heritage and at the same time make it far more accessible than it could have been before.”15

The next bit gets at some of my concerns:

“it is one relatively small computer program, set up to run in each storage machine of an ever growing network.”16

“And rather than having to be run by the government, or some other large untrustworthy corporation, it can be dispersed under local ownership to serve entire nations and eventually the whole world.”17

Documents are pointers into the changing web of data #

Documents are being defined as a series of pointers. Links are being defined as connections between documents. Possibly I’m confusing my understanding of HTML anchor elements with the use of the term “links” in this context.

Where I start to question the project’s approach to storage #

“Why should any individual have to worry about the safety of all those floppy disks—let alone those precious family photographs—when they can be safely stored in a public utility? Just as the ‘Mini Self-Storage’ facility now proliferates across the country, this will be a public-access facility for recordings, writings, pictures, audio and video and movies, and whatever other data people want to use it for.”18

I guess my issue is that in hindsight they seem to be describing what’s turned into “the cloud”.

“Offices will be paperless, as soon as people figure out what this means. (Hint: new ways of structure to map the true connections between documents.)”19 I like this so much, except: I’m too much of a pessimist to think that digital is more robust than paper; the document storage faculties aren’t benevolent public organizations, documents can be deleted, edited without warning, purchases disappear, etc.

The 2020 vision (seen from the year 2026) #

Writing in 1987:

“Forty years from now (if the human species survives), there will be hundreds of thousands of file servers—machines storing and dishing out materials. And there will be hundreds of millions of simultaneous users, able to read from billions of stored documents, with trillions of links among them.”20

He got that right.

“The system proposed in this book may or may not work technically on such a scale. But some system of this type will, and can bring a new Golden Age to the human mind.”21 (We did get some system, there are some benefits, for example, I’m reading the book on the Internet Archive, but it’s questionable if this is a new Golden Age for the human mind. I’m not saying it isn’t. At the very least it’s a messy situation.)

We need you #

The Xanadu group still needs brilliant people looking for adventure and challenge, long hours, low pay, accidental food, and a small chance of fame and fortune. We have to save mankind from an almost certain and immediately approaching doom through the application, expansion and dissemination of intelligence. Not artificial, but the human kind. To humankind.22

Hypertext (Literary Machines chapter 1 (Hypertext)) #

Spoken language is a series of words #

“Spoken language is a series of words, and so is conventional writing. We are used to sequential writing, and so we come easily to suppose that writing is intrinsically sequential. It need not be and should not be.”23

Arguments for breaking away from sequential presentation #

“There are two outstanding arguments for breaking away from sequential presentation. One is that it spoils the unity and structure of interconnection. The other is that it forces a single sequence for all readers which may be appropriate for none.”24

Spoiling the unity and structure #

“The sequentiality of text is based on the sequentiality of language and the sequentiality of printing and binding. These two simple and everyday facts have let us to thinking that text is intrinsically sequential….But sequentiality is not necessary. A structure of thought is not itself sequential. It is an interwoven system of ideas (what I like to call a structangle). None of the ideas necessarily comes first; and breaking up these ideas into a presentational sequence is an arbitrary and complex process. It is also often a destructive process…”25

Forcing a sequence that’s inappropriate for all readers #

“People have different backgrounds ans styles….Yet sequential text, to which we are funneled by tradition and technology, forces us to write the same sequences for everyone, which may be appropriate for some readers and leave others out in the cold….it would be greatly preferable if we could easily create different pathways for different readers…”26

See notes / Scatter technique for an alternate approach to the same problem.

Nonsequential writing on paper #

Nonsequential writing on paper: magazine layouts, arrangements of poetry, pieces of writing connected by lines…

Nonsequential writing for digital media #

Chunk style hypertext #

The most obvious form of nonsequential writing is chunk style hypertext.27 The reader moves through the text by reading one chunk, then following a link to the next chunk, etc.

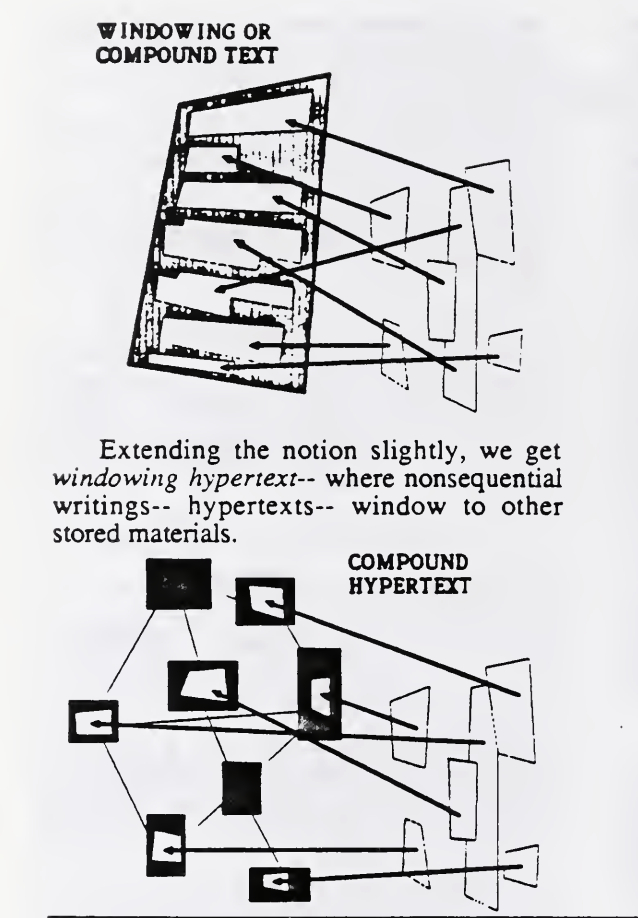

Compound text otherwise known as windowing text #

Compound text is where materials are viewed and combined with others.

“A good way of visualizing this is as a set of windows to original materials from the compound textx themselves. Thus I prefer to call this windowing text.”28

Nonsequential writing as it exists on the modern internet #

It’s not clear to me how Ted Nelson would view the current state use of anchor tags on the modern web. For example, how about Wikipedia’s approach of expanding content when you hover over a wiki-link? I know that from my point of view the common approach to links is disjointed and breaks context. That’s the problem that I’m trying to solve.

Hypertext defined #

“By hypertext I simply mean non-sequential writing. A magazine layout, with sequential text and inset illustrations and boxes, is thus hypertext. So is the front page of a newspaper, and so are various programmed books now seen on the drugstore stands…”29 (The “choose your own adventure” books from my childhood.)

“In fact, however, we constantly depart from sequence, citing things ahead and behind in the text. Phrases like ‘as we have already said’ and ‘as we will see’ are really implicit pointers to content elsewhere in the sequence.”30

What’s hard about writing #

“There are basically two difficulties in writing sequential text: deciding on the sequence—there are so many possible connections!— and deciding what’s in and out. Both of these problems go away with hypertext. You no longer have to decide on sequence, but on interconnective structure….You no longer have to decide what’s in or out, but simply where to put things in the searchable maze.”31

What’s tricky about reading #

“In reading works of non-fiction, the active reader often skips ahead, jumps around, ponders about background material. These initiatives are useful and important; if we provide pathways to help active reading, it will be possible to enhance initiative and speed comprehension.”32

Two styles of hypertext organization #

Presentation and effect #

“One style of hypertext organization is based on its possible effect on the reader. The connective structure is a system of planned presentations which the reader may traverse. Variant sequences and alternative jumps will be contrived for how they look, feel and get ideas across.”33

Lines of structure #

“The other (other being presentation and effect ) style of hypertext organization is based on simply representing the structure of the subject, with possible directions of travel mapping the relations in the network of ideas being represented. The internal relations of the subject are thus represented in the connective relations of the hypertext. This is simpler than calculating the effect on the reader, since the author is only concerned with analyzing and representing what the structure really is, and the reader is exploring the structure as he or she explores the text.”34

The problem of orientation #

“There are tricky problems here (here being what’s outlined in two styles of hypertext organization ). One of the greates is how to make the reader feel comfortable and oriented. In books and magazines there are lots of ways the reader can see where he is (and recognize what he has read before)….These incidental cues are important to knwing what you are doing. New ones must be create to take their place….How these will relate to the visuals os tomorrow’s hot screens is anybody’s guess…”35 (Me in 2026, if it had worked out I probably wouldn’t be reading/writing this today.)

Improved representation of thought #

“It is my belief that this new ability to represent ideas in the fullness of their interconnections will lead to easier and better writing, easier and better learning, and a far greater ability to share and communicate the interconnections among tomorrow’s ideas and problems. Hypertext can represent all the interconnections an author can think of; and compound hypertext can represent all the interconnections many authors can think of…”36

I keep coming back to the idea of “what went wrong?” Maybe it’s just me, or a subset of readers, but I don’t find existing representations of the interconnections between ideas in apps like Obsidian (which I otherwise like), or Wikipedia to be all that useful. I mostly find them to be disorienting. It could be that I’m not smart enough, or smart in the right way, to make use of them. In any case, that’s the problem I’m wanting to solve/improve on.

The school problem #

The curriculum #

“The very system of curriculum, where the world’s subjects are hacked to fit a schedule of time slots, at once transforms the world of ideas into a s c h e d u l e. (‘Curriculum’ means ’little racetrack’ in Latin.”37

“A curriculum promotes a false simplification of any subject, cutting the subject’s many interconnections and leaving a skeleton of sequence which is only a carricature of its rechness and intrinsic fascination.”38

Teacher as Feudal Lord #

“The world of ideas is carved into territories, and assigned as fiefdoms to individuals who represent these territories (called Subject); these lords and ladies in turn impose their own style and personality on them.”39

“The teacher controls access to the subject under his or her viewpoint. If you find this viewpoint unfriendly, unpleasant or confusing, that subject becomes closed to you forever.”40

Problems caused by the curriculum and teacher #

“These two principles ( The curriculum , Teacher as Feudal Lord )…effectively guarantee that whatever is taken in school becomes and remains uninteresting. Everything is intrinsically interesting, but is drained of its interest by these processes.”41

“What is perhaps even worse, this system imbues in everyone the attitude that the world is divided into ‘subjects;’ that these subjects are well-defined and well-understood; and that there are ‘basics,’ that is a hierarchy of understandings which must necessarily underpin a further hierarchy of ‘advanced ideas,’ which are to be learned afterward.”42

This marks the end of my notes from Literary Machines chapter 1 (Hypertext). Continued at notes / Literary Machines chapter 2 .

-

Ted Nelson, “Literary Machines,” (Edition 87.1), p. 20 (0/1). ↩︎

-

Ted Nelson, “Literary Machines,” (Edition 87.1), p. 20 (0/1). ↩︎

-

Ted Nelson, “Literary Machines,” (Edition 87.1), p. 21 (0/2). ↩︎

-

Ted Nelson, “Literary Machines,” (Edition 87.1), p. 21 (0/2). ↩︎

-

Ted Nelson, “Literary Machines,” (Edition 87.1), p. 21 (0/2). ↩︎

-

Ted Nelson, “Literary Machines,” (Edition 87.1), p. 22 (0/4). ↩︎

-

Ted Nelson, “Literary Machines,” (Edition 87.1), p. 22 (0/4). ↩︎

-

Ted Nelson, “Literary Machines,” (Edition 87.1), p. 23 (0/5). ↩︎

-

Ted Nelson, “Literary Machines,” (Edition 87.1), p. 23 (0/5). ↩︎

-

Ted Nelson, “Literary Machines,” (Edition 87.1), p. 23 (0/5). ↩︎

-

Ted Nelson, “Literary Machines,” (Edition 87.1), p. 23 (0/5). ↩︎

-

Ted Nelson, “Literary Machines,” (Edition 87.1), p. 23 (0/5). ↩︎

-

Ted Nelson, “Literary Machines,” (Edition 87.1), p. 24 (0/6). ↩︎

-

Ted Nelson, “Literary Machines,” (Edition 87.1), p. 24 (0/6). ↩︎

-

Ted Nelson, “Literary Machines,” (Edition 87.1), p. 24 (0/6). ↩︎

-

Ted Nelson, “Literary Machines,” (Edition 87.1), p. 24 (0/6). ↩︎

-

Ted Nelson, “Literary Machines,” (Edition 87.1), p. 24 (0/6). ↩︎

-

Ted Nelson, “Literary Machines,” (Edition 87.1), p. 28 (0/10). ↩︎

-

Ted Nelson, “Literary Machines,” (Edition 87.1), p. 29 (0/11). ↩︎

-

Ted Nelson, “Literary Machines,” (Edition 87.1), p. 30 (0/12). ↩︎

-

Ted Nelson, “Literary Machines,” (Edition 87.1), p. 30 (0/12). ↩︎

-

Ted Nelson, “Literary Machines,” (Edition 87.1), p. 31 (0/13). ↩︎

-

Ted Nelson, “Literary Machines,” (Edition 87.1), p. 46 (1/14). ↩︎

-

Ted Nelson, “Literary Machines,” (Edition 87.1), p. 46 (1/14). ↩︎

-

Ted Nelson, “Literary Machines,” (Edition 87.1), p. 46 (1/14). ↩︎

-

Ted Nelson, “Literary Machines,” (Edition 87.1), pp. 46,47 (1/14,1/15). ↩︎

-

Ted Nelson, “Literary Machines,” (Edition 87.1), p. 47 (1/15). ↩︎

-

Ted Nelson, “Literary Machines,” (Edition 87.1), p. 47 (1/15). ↩︎

-

Ted Nelson, “Literary Machines,” (Edition 87.1), p. 49 (1/17). ↩︎

-

Ted Nelson, “Literary Machines,” (Edition 87.1), p. 49 (1/17). ↩︎

-

Ted Nelson, “Literary Machines,” (Edition 87.1), p. 50 (1/18). ↩︎

-

Ted Nelson, “Literary Machines,” (Edition 87.1), p. 50 (1/18). ↩︎

-

Ted Nelson, “Literary Machines,” (Edition 87.1), p. 50 (1/18). ↩︎

-

Ted Nelson, “Literary Machines,” (Edition 87.1), p. 50 (1/18). ↩︎

-

Ted Nelson, “Literary Machines,” (Edition 87.1), p. 50 (1/18). ↩︎

-

Ted Nelson, “Literary Machines,” (Edition 87.1), p. 51 (1/19). ↩︎

-

Ted Nelson, “Literary Machines,” (Edition 87.1), p. 52 (1/20). ↩︎

-

Ted Nelson, “Literary Machines,” (Edition 87.1), p. 52 (1/20). ↩︎

-

Ted Nelson, “Literary Machines,” (Edition 87.1), p. 52 (1/20). ↩︎

-

Ted Nelson, “Literary Machines,” (Edition 87.1), p. 52 (1/20). ↩︎

-

Ted Nelson, “Literary Machines,” (Edition 87.1), p. 52 (1/20). ↩︎

-

Ted Nelson, “Literary Machines,” (Edition 87.1), p. 52 (1/20). ↩︎